Urban space

At the turn of the 18th-19th centuries, Debrecen was the most populous and wealthy and influential town in the Kingdom of Hungary, and what rendered her rather special is that it cannot be forced into any of the pigeonholes of a clear-cut urban typology. This, however, does not mean exceptional character, but a kind of historically developed complexity, without the exploration of which it is impossible to understand the modernization/marketization processes in the city that took place from the turn of the 18th-19th centuries onwards. The city arriving at the doorstep of the "brave new world" was called an oversized village, the city of hard-headed peasant-bourgers, that is, cívis, a city of merchants, the "Calvinist Rome”, or even the "guardian-city of freedom” –owing to her role in the Hungarian war of Independence (1848-49). Which view is correct? Which aspect of it is the real one?

We are not at all in a position to give the right answer, if just one face were to be portrayed as the decisive one. Novelist Magda Szabó grasped the essence of contemporary Debrecen when she wrote: „Debrecen turns her three faces towards me, one looking back into the past, the other looking me in the eye, the third is looking forward into the future. I consider all three my own but none without the other two.”

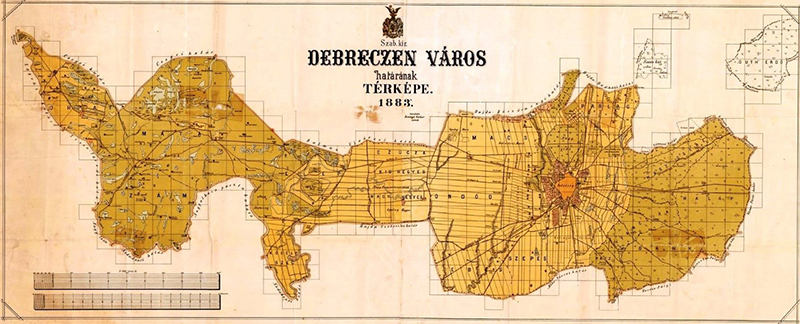

The inner core of the settlement was sorrounded by 166,286 cadastral hold (=1 yoke =1.42 acres) field confines of 95,720 hectares, that is, 957 square kilometres around the city that got into municipal possession by right of different means of acquisition or obtained the title of utilization.

Map of Debrecen free royal city’s intra- urban area and her other confines, 1883

The actual territory of Debrecen together with her land-holdings was the second biggest in the Carpathian basin, second only to the municipality of Szabadka (Subotica), (974 square kilometers) in close approximation in size to the smallest county of Esztergom (1077 square kilometres). The extensive land-holdings of the city of Debrecen constituted the bulk of her revenue sources. The second major source of revenue was derived from the city’s rights of adrowson and its earlier benefices (such as liquor licence, market and fair charges, fishing, the sale of salt and tobacco). The third pillar of the the city’s economy was handcraft industry and commerce.

The weight of merchantry and the market-oriented merchandizing mentality is shown by the very circumstance that neary half of her land-holdings were acquired through business deals, purchased or used as morgaged estates (acquired properties, goods and chattels estates that had remained in the utilization of the city on the long run.)

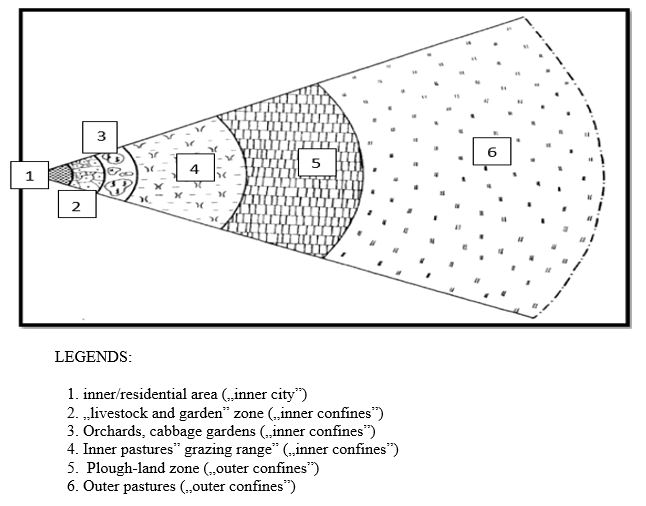

The plot structure of the land, the characteristics of market-town development in the plains region had determined the economy of the city and its spatial arrangement up to the middle of the 19th century.

The inner core of the city sorrounded by palisade and ditch took up an area of 320 hectares but it was less than 4 per mille of the total area of the city, but could be considered as fairly large relative to the 50,000 strong population (that is why it was often depicted as an oversized village).

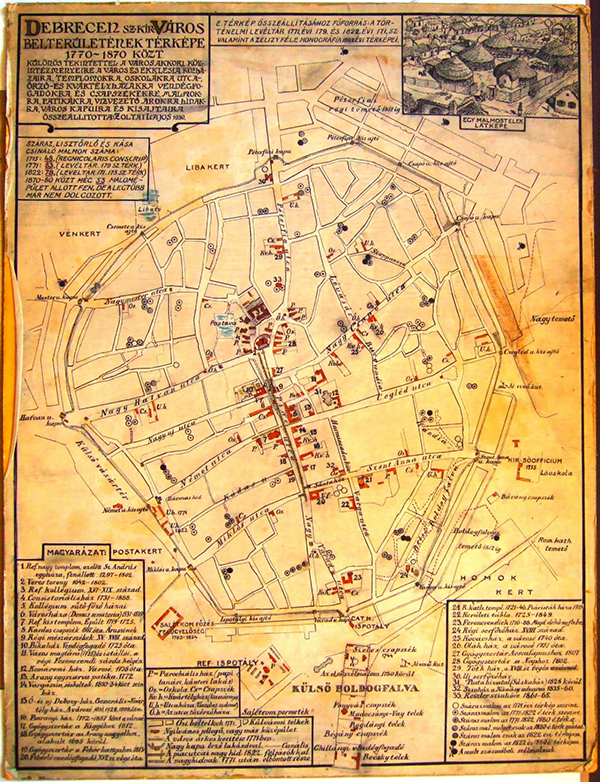

Lajos Zoltai’s reconstruction of the inner city of Debrecen as it took shape between 1770 and 1870.

According to the consolidated system of privileges only citizens with unlimited rights were allowed to own plots and houses in the city. In 1848, a total of 3500 taxable houses were registered, that is, the number of civis citizens is estimated to be around this figure. The plot arrangement secured for the holders of inner city plots further land-holdings in different zones around the city with diverse land-utilization goals.

The conceptual scheme of spatial and field utilization based on the rigid scheme of plot-structure in Debrecen

The city as manorial lord also held villeins’ land units (8,000 hectares) in three nereby villages that lay near to -, but outside her confines. The rigid value-system resting on feudal privilege, the main and traditional economic activity and the plot structure and land utilization, as well as the revenue generated by them constituted the main motive force of the uncompromising conservative attitude dismissive of changes even as late as the early 19th century.

At the same time, municipal resources drawn from manorial rights, dues, which included those from taverns, butchers’shops, (and in earier times even excise revenues from the sale of salt and tobacco) as well as from the business utilization of acquired land-holdings altogether led to guarding privileges as a general principle, but also to a fairly practicable down-to-earth market-oriented business-minded behaviour and attitude.

At the turn of the 18th-19th centuries, however, the change taking place in market conditions, the development of credit conditions and trade in commodities and increasing competition gaining prevalence even in the framework of a privilege sytem favourably influenced the shaping of a multi-level interregional, regional and sub-regional and local market-hub role resulting in the predisposition to modern capitalist market conditions.

In the mid-19th century in the wake of the Reform Age and the legislation of 1848, the unfolding process of modernization found a city which harboured remarkable growing transitional tensions that contained both privilege-guarding satus-quo conservatism and pragmatic market mindedness as well as those who desired and endeavoured to take advantage of modern market conditions.