Social dimensions

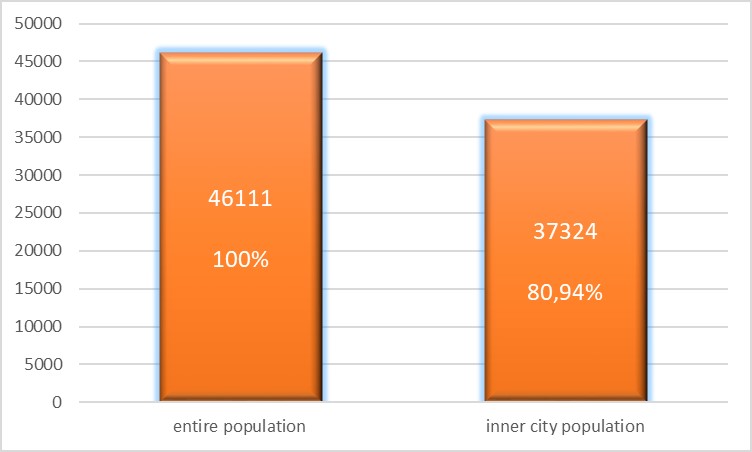

Our GIS database does not cover the entire area of the civis city, containing only the data of the compactly populated and once stockaded area of the inner city that covered 4 per mille of the total territory of the city providing residential space to four-fifths of the total of her population.

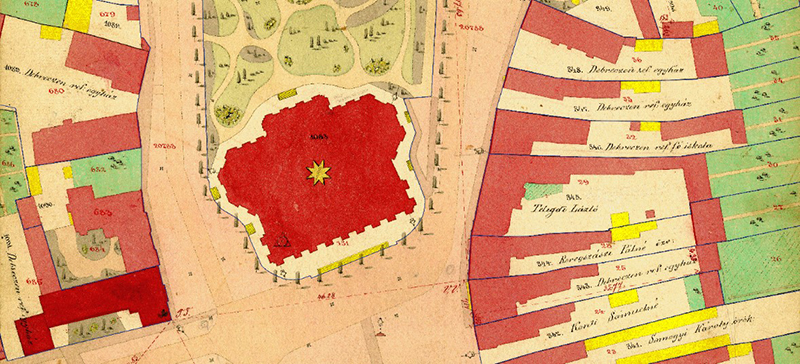

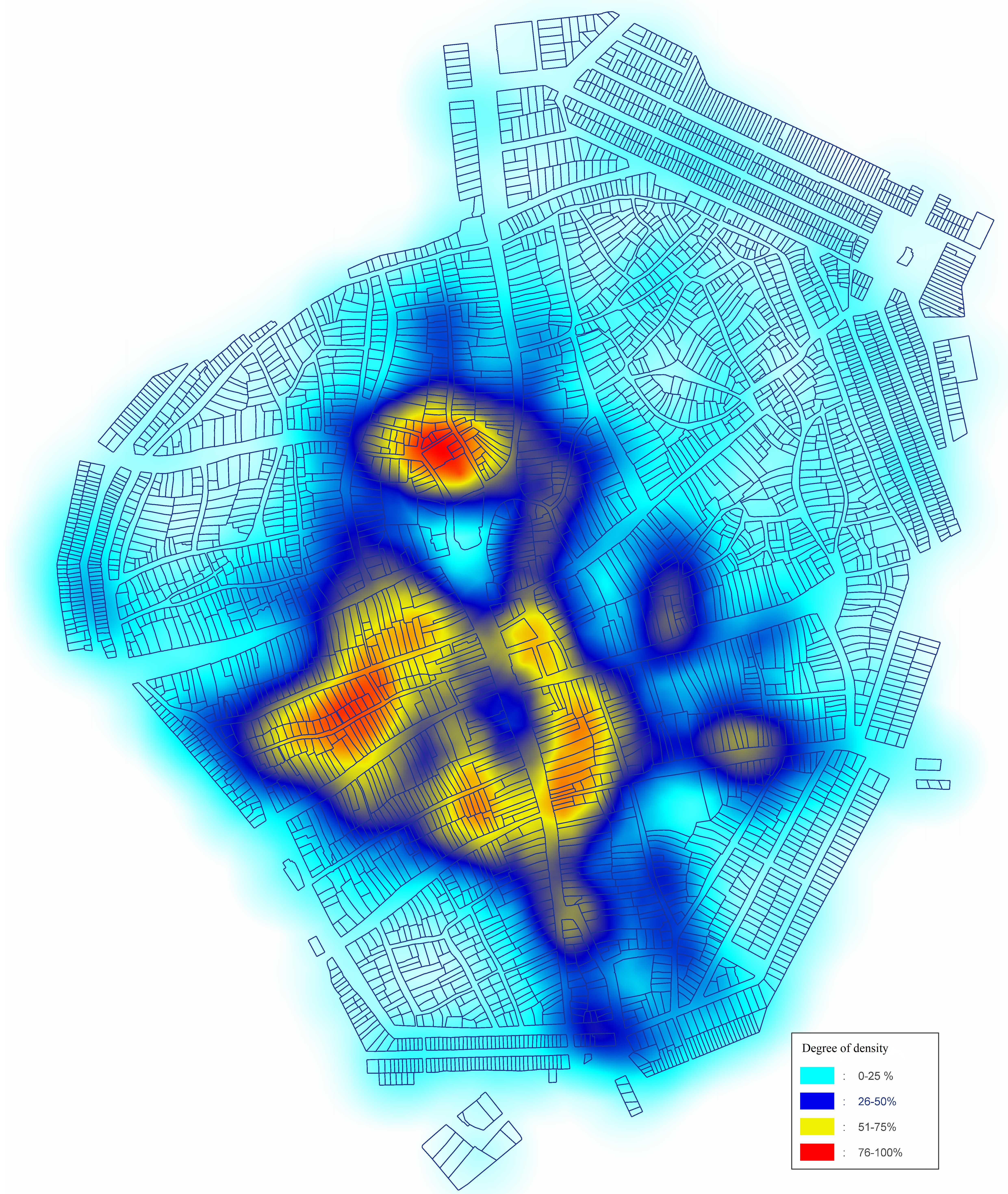

Distribution of the population of Debrecen, 1870

Research is indeed limited to this compactly populated area, still identified as the inner city area even after the demolition of the city limit stockade without any further denotation.

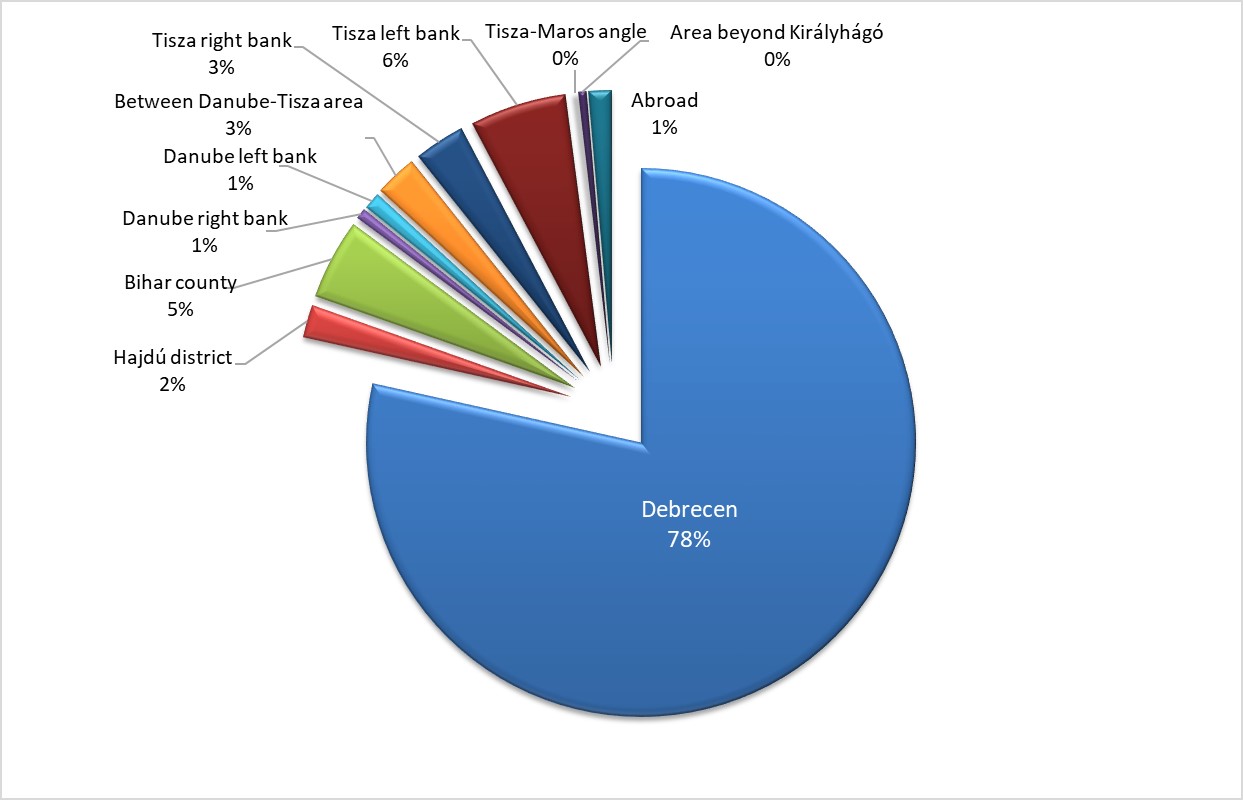

Based on the data gleaned from the databases, 78% of the intra-urban residents identified Debrecen as their birthplace, the rest had been born outside Basahalma and had moved into the city of Debrecen. Our case-studies show that the in-migrants’ share of slightly over 20% points to a slow and trickling dynamics of migration that had been taking place in the previous two decades. Out of the 22% of in-migrant settlers, the majority (21%) had arrived from the territory of the Kingdom of Hungary and only 1% had been born outside the state’s borders.

The relative majority of the in-migrants had arrived from the vicinity of the confines of the city – 2% from the Hajdú District, 5% from Bihar county and from the multi-stage course of the Jewish in-migration "unterland” trail from counties lying along the two banks of river Tisza using the categorization of the official population census . Also significant was the number of people coming from other parts of the more middle-class oriented regions which also included the capital city making up 3% while from other parts of the home-country and Transylvanian regions in-migration remained steadily low.

Compostion of Debrecen intra-urban population broken down by place of birth

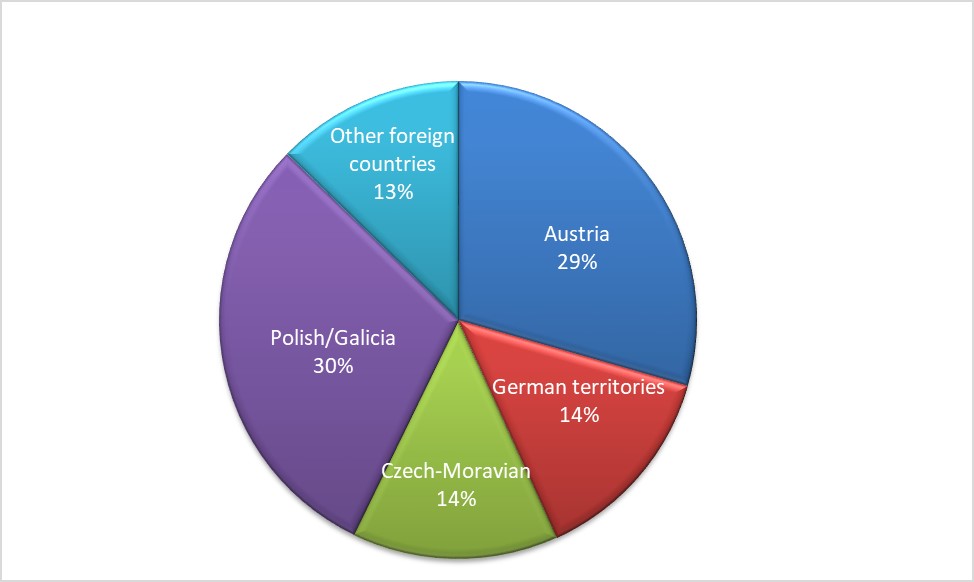

In-migrant settlers in Debrecen having come from abroad did not amount to a total of 50, however their numerical representation was far surpassed by their role in the economic life of the city. The contingent of in-migrants from abroad was dominated by those who had arrived from Galician-Poland and the Trans-Leithan regions and half as many had arrived from Bohemian, Moravian and German lands and the same number from other countries in Europe altogether.

Distribution of in-migrant settlers from abroad in intra-urban Debrecen, 1870

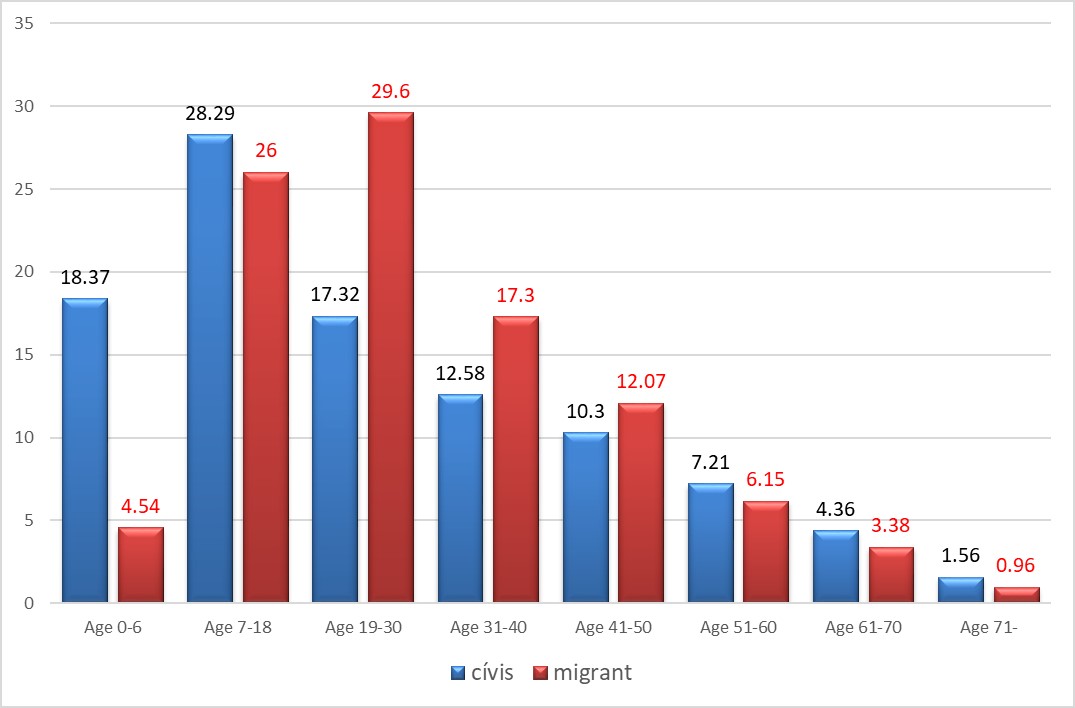

HOW OLD WERE THEY? – WHAT WAS THE AGE COMPOSITION OF CIVIS AND IN-MIGRANT POPULATION LIKE?

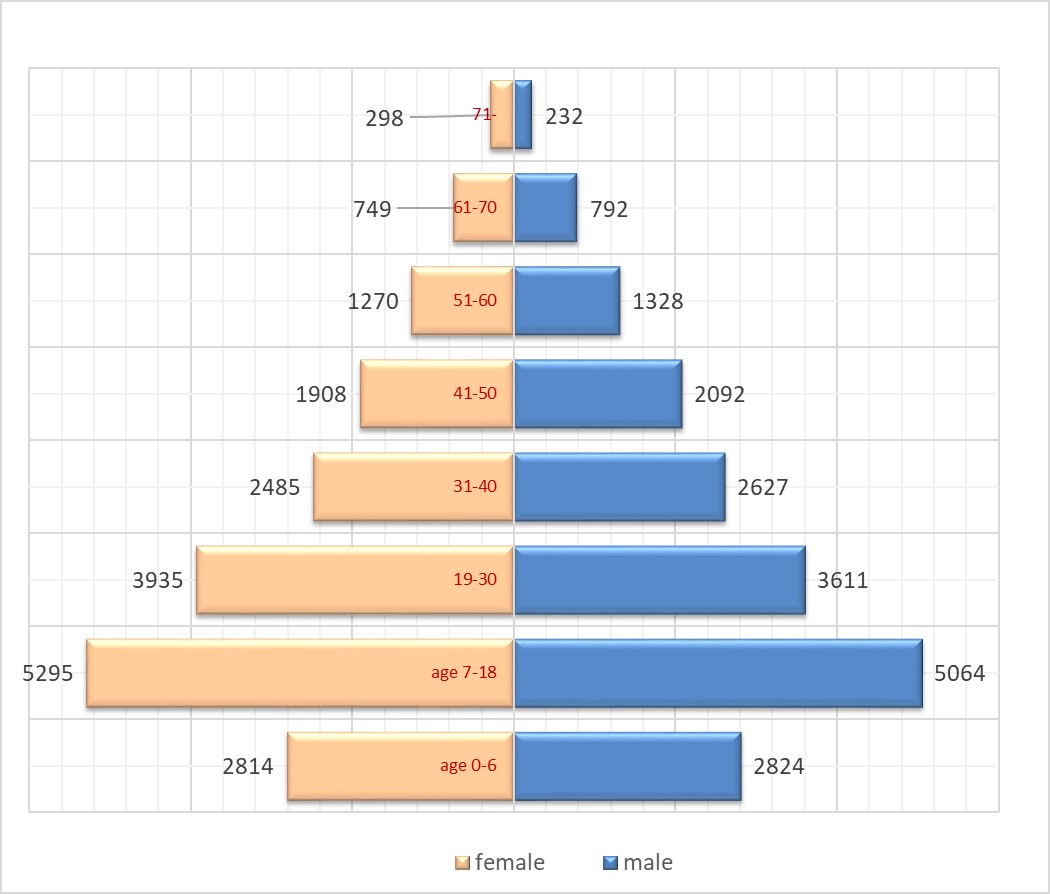

Some distortion is caused in the age-pyramid representing the age-composition of Debrecen citizens residing in the intra-urban area of the city by the fact that the under 30 years of age was not grouped into 10 year-cohorts in accordance with later literacy studies but into school-age 0-6, and public education 7-18 age groups each. Even with these modifications, it can be seen that the age pyramid of Debrecen population, at the time of census-taking, assumed the shape of a pyramid characteristic of a steadily growing population betraying features of the early stage of a demographic transition. The male-female ratioin the population was very well balanced: There were only 184 more women than men. Women showed a majority in the fertile age-groups as well as in the most senior (over 71) age-groups. Among the males, however, a majority was found in the 31-70 age-groups.

Age-pyramid for intra-urban Debrecen, 1870

If we look at the overall age composition of the indigenous and allochthonous population, the in-migrant population was, on the whole, younger than the recipient population. Especially amongst the economically active age-groups (19-30; 31-40 and less in the 41-50 group), but those of better income and business potentials, one can see an apparently higher proportion of younger individuals among the in-migrants. The Debrecen-born are, on the other hand, predominant among the youngest school-age population, but also in a relative majority among the apprentice-age (7-18) and older age-groups (51-60; 61-70 and 71<), too.

Percentage proportions in the intra-urban area of Debrecen, 1870

The oldest resident in Debrecen in 1870 was a 98-year-old widow of the Reformed Calvinsit denomination, Mrs. Ferenc Tót, who resided in the front section of a duplex, at plot no. 2240 in Cser street. As she was a beggar and recipient of municipal alms, the owner of the house also a widow, a 43 year-old land owner, admitted the former into her family of five children of her own in a bedsitter +kitchen+pantry unit.

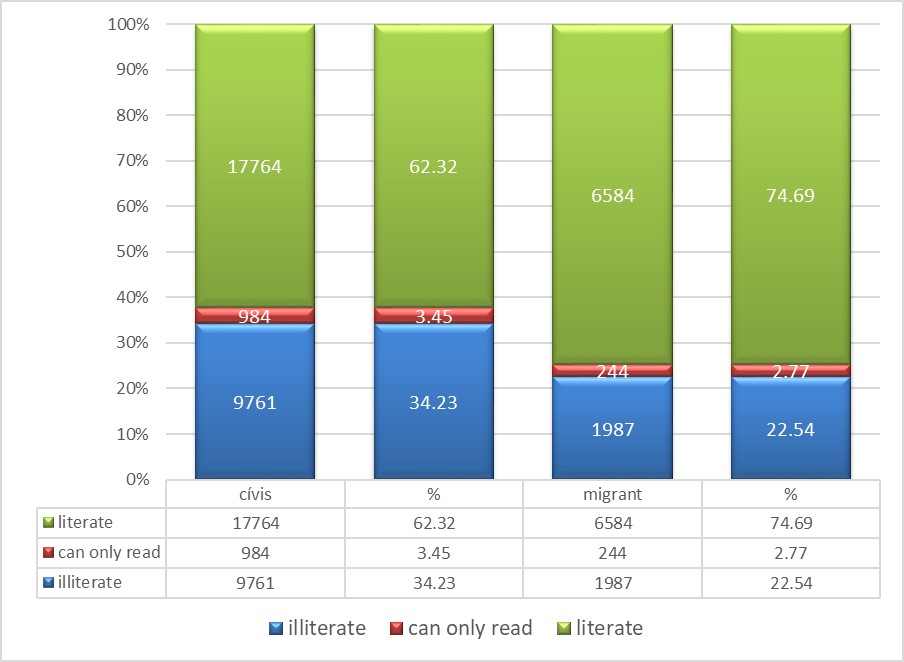

GENERAL CONDITIONS OF CULTURE - LITERACY OF THE CIVIS AND IN-MIGRANT POPULATION

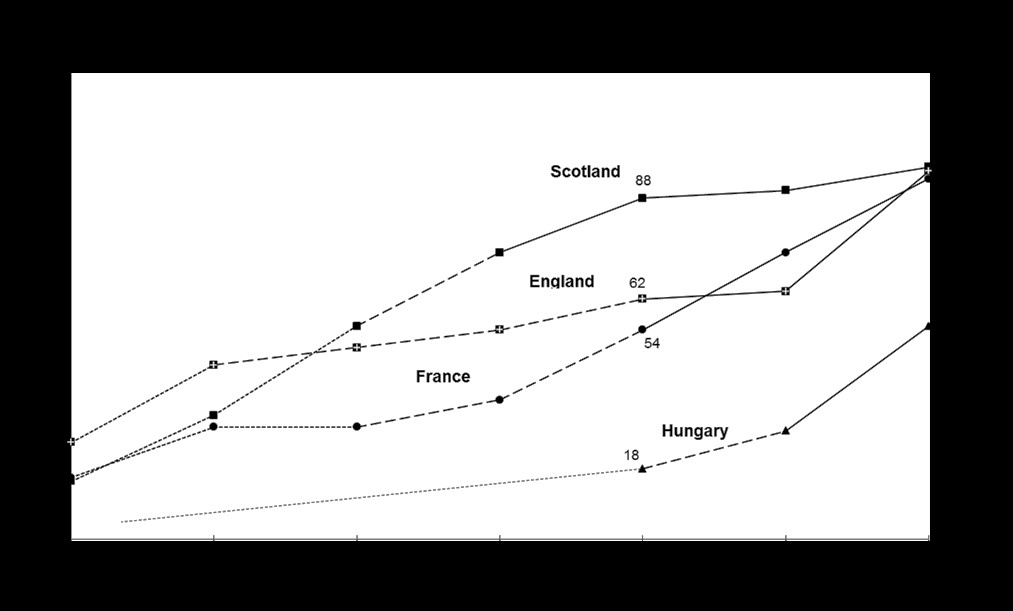

The 1869 census of population distinguished three levels of literacy. Apart from the illiterates, a special category was set aside for those who were only able to read but not able to write, and a third rubric for those capable of both reading and writing. The advent of school-based primary education resulted in the literacy of masses of people in the more developed regions of Europe between 1750 and 1850 in connection with the advance of industrial modernization. In the decade of the Austro-Hungarian compromise, on average two-thirds of the population already got fully literate in the more developed regions of Europe and the process of alphabetization had essentially become complete in those regions. Hardly a third of the adult male population in the kingdom of Hungary had accomplished alphabetization with one-fifth of the population remaining illiterate in the years proceeding World War I.

Thanks to the school system of Debrecen, the same period saw the attainment of literacy by nearly two-thirds of her adult population. Within the total of the intra-urban population literacy rate surpassed the two-thirds (2/3) level and among the people older than 6 years of age literacy approximated 75 % . At the time of the census of population a 10 % difference was registered to the advantage of the in-migrant population (63.23%-74.69%). The difference detected in erudition can be attributed partly to contemporary conditions – the 6-year-old or younger age-groups were significantly under-represented among the in-migrants. The difference in the rate of basic culture established among the in-migrant population is undoubtedly an outcome of their higher schooling.

The alphabetization of adult male population

The rate of alphabetization among the intra-urban population of Debrecen by place of birth, 1870

WHO LIVED WHERE? – CONDITIONS OF RESIDENTIAL SEGREGATION AND NEIGHBOURHOOD RELATIONS

The GIS database will perhaps offer the most new and exciting opportunities: How in-migration gave rise to changes in the urban residential distribution, where did the civis population reside?

Did in-migration result in changes in residential conditions? Where did in-migrants settle? Was there a strong residential segregation? What kind of neighbourhood patterns took shape between the recipient and in-migrant populations?

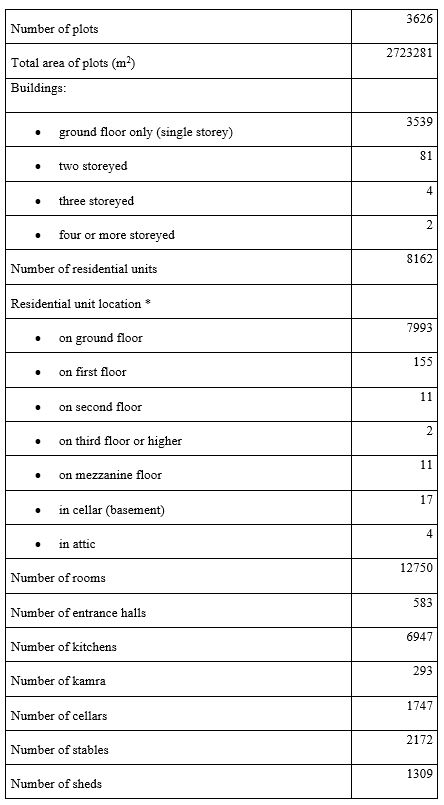

Plots and residential conditions in Debrecen intra-urban area, 1870

Out of the 3626 plots in the census survey there are 20 plots for which no census survey data could be found in the census survey sheets. The total of plot land area was further enhanced by public places (common), therefore the total of the studied area amounted to 3,835,224 square metres.

The digital base-map of the database contains the numbering of plots (house numbers) and the plot boundaries within the inner-city limits, the bordering lines of both solid and wooden structures, the names of public places as well as the bordering lines of blocks and city quarters and the outer boundary-line that lay inside the “turnpikes”.

The digital base-map of inner-city Debrecen with its plot- and outer boundary line on rastered layers 1870

The hand-drawn and subtitled surfaces can be displayed on separate tone-block surfaces, which contain with a slight time-delay (1872) the green (park, trees and bush) areas and characteristic buildings in public places (public halls, public lighting, lines of paved walk-ways) and the data of the plot-owners in addition to the information made available in the base-map

The Big Church and its surroundings on rastered surface of the manuscript map

The data available in the demographic survey were attached to the households/residential units in the plots of the base-map, which, in turn, facilitates queries by plots, households, and individuals as well as certain interconnections between them. Apart from the results of the queries being registered in a data tabulation, they can be shown in the base-maps (mapping). Moreover the GIS software also permits inquiries into certain aspects of spatial relations of which the historian can most profitably use the measurement and visualization of density (frequencies found within a specified place).

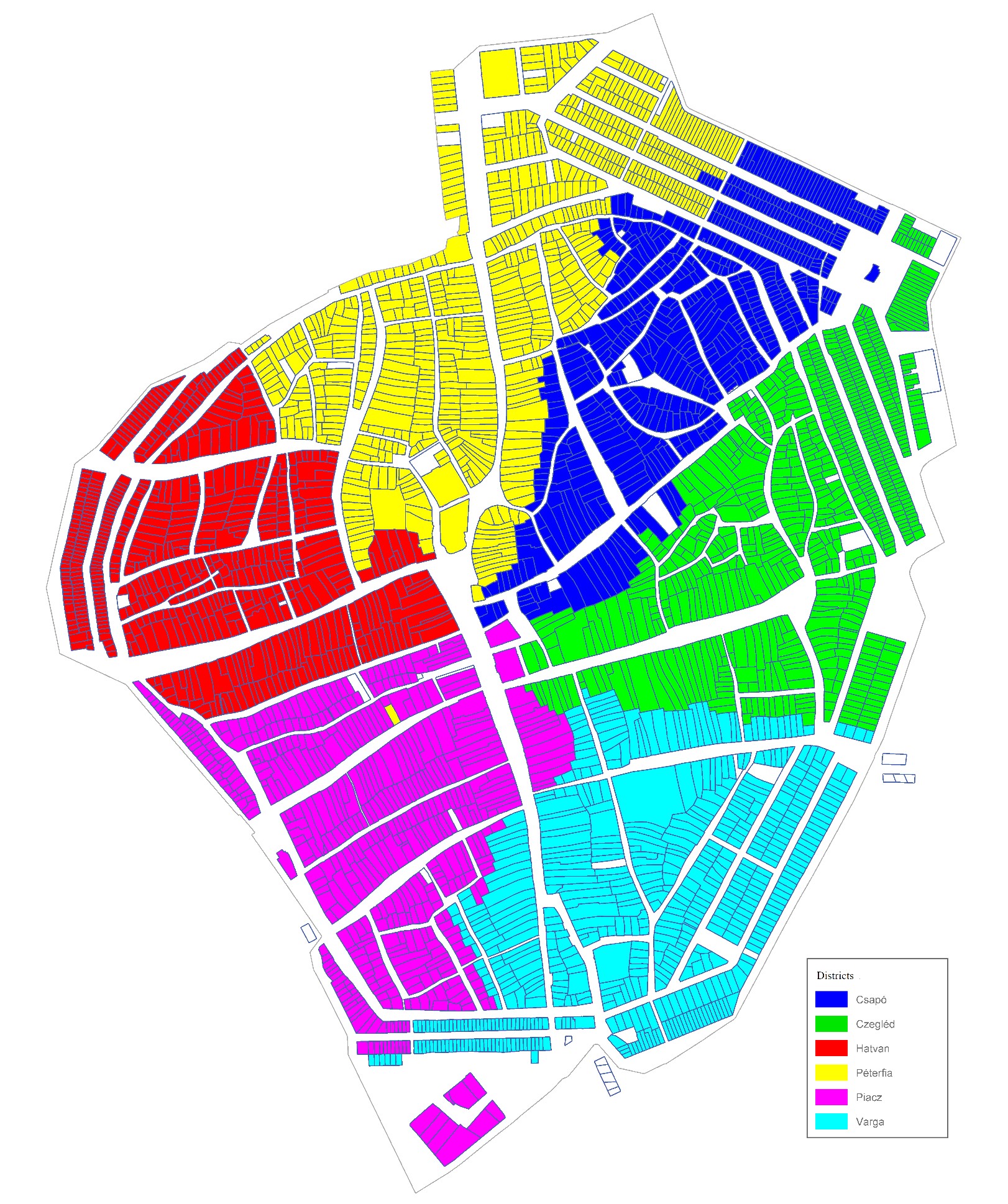

In accordance with the internal administration of the city and its role in shaping the district boundaries, the city was organized into six “derék”, that is around six major thoroughfares (streets). The destricts bearing the name of “derék” streets were each traditionally authorized to have their subdivisions or sectors, the “platoons” (tized) and to rely on them for purposes of administration and/or law enforcement. Five of them for each district in the traditional inner city amounting altogether to 30, while on the outskirts adjacent to the old city boundary containing new plots they were divided into 11 external tized each of which organically adhered to its inner district both in naming and numbering.

House numbers started with No.1, the city Hall, then continued on the northern side of Cegléd street then on to the Csapó street -, Hatvan street -, Piac street – and then Varga street precincts covering a great circle back to the Cegléd district which then continued in the external tizeds. It was only after the 1898 replanning of the city that they returned to the method of numbering plots and houses used before 1845, that is, starting numbering houses and plots from the beginning of the street down.

Districts in Debrecen, 1870

Because of the queries relating to the plot and household level or queries to be initiated from place and targeted, at will, at a designated area, inquiry by district has less significance, whereas in professional literature this approach has had greater significance owing to data aggregation and has got consolidated methodology as well as findings that are worth taking into consideration for comparative studies.

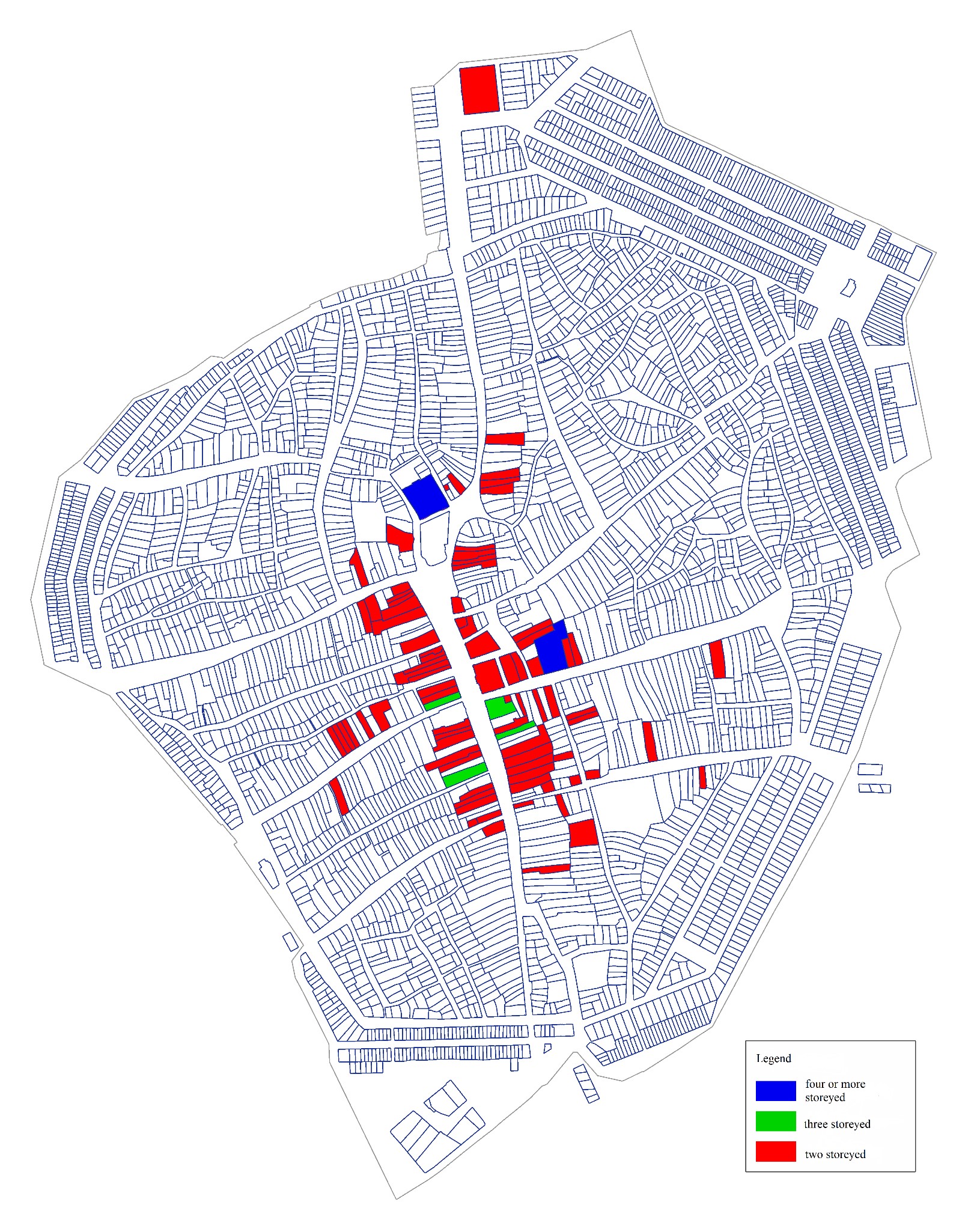

Debrecen still presented the picture of a cityin 1870 that had grown from a typical market-town of the plains, only the church spires and the mass of a few multi-storey buildings as well as the siluettes of grain mills in the inner districts and a few smokestacks in the outskirts stood out of the rest. With the exception of 87 structures, buildings in Debrecen were all one-level constructions. 81 were two-level buildings and most of the 4 three- level ones were to be found in the core of the city, which, from this point of view, also marks the beginning of city-wards urban development – but it simultaneously shows its limited nature and its spatial shrinking. One of the two taller buildings in the census sheets was registered under the no. 1062 plot was the Reformed College of Debrecen containing 1 chapel, 25 classrooms, 7 library rooms on the three floors over the ground floors, 111 students were taken stock of as living in the rooms of the college.

The other four-level building registered under No. 20. one found none other than the modest municipal theatre designated as “városi színház”. The then half a decade old “permanent stone” municipal theatre opened on October 7, 1865 with staging the play “Bánk Bán” had become one of the outstanding and decorative edifices, a proof of how hard civis citizens were to please with respect to culture and of the fact, ’’they could afford it”. Two official apartments were registered in the municipal theatre building, one occupied by the theatre’s superintendent with his wife and the widowed librarian of the theater. The other was inhabited by one of the celebrated actors of the period, József Szabó.

The Calvinist Reformed Big Church registered under plot no. 1603, which happened to rise higher than those edifices registered as four-levelled registered by the census taking, got registered as a ground-level building by the census taking commissioner, while the only residential unit in it, that of the town watchman was recorded as located in the tower or the attic. It is of special interest that, at the time of the census taking, the only tower watchman was called none other than Mihály Nyilas.

Ground-level and multi-level buildings in Debrecen, 1870

PROPRIETORSHIP – HOUSES AND OWNERS

1. Up to 1849 only individuals with Debrecen citizenship rights had been lawfully eligible to

possess inner city plots whereas those without citizenship rights were only entitled to get

residential units only in the “back yard” from the proprietor civis.

In 1840 the members of the Israelite denomination were granted the permission to lawfully move

into the city, but it did not automatically grant the right of acquiring property as well. As a

result of the Imperial Decree of February 18, 1860 and the legislative actions of the Council of

the Lord Chief Justice the window of opportunity for property acquisition opened for a short

temporary period, it was only the time of the Austro-Hungarian Compromise that substantially

legalized property acquisition without regard to denomination or other considerations.

2.The citizens fully entitled and capable of possessing real estate constituted the “upper

class” while the inner city cotters or even less entitled outsiders living “outside the

turnpikes” constituted the lower classes.

3. For nearly a decade after 1849, it was obtaining Debrecen citizen’s rights that secured a

straight opening to the acquisition of property for individuals belonging to any other

non-privileged community. This legal tradition gradually vanished in Debrecen in the 1850s, but

a strict screening of in-migrants survived.

4.Only 2-3 years were open for effective property acquisition in the case of inner-city real

estate in Debrecen, although there had been word going around about deals on the sly especially

in relation to plots that were used to store wares prior to the great Debrecen Fairs or about

rental contracts for the on-location storage of the wares of the Jewish pedlars from

Hajdúsámson.

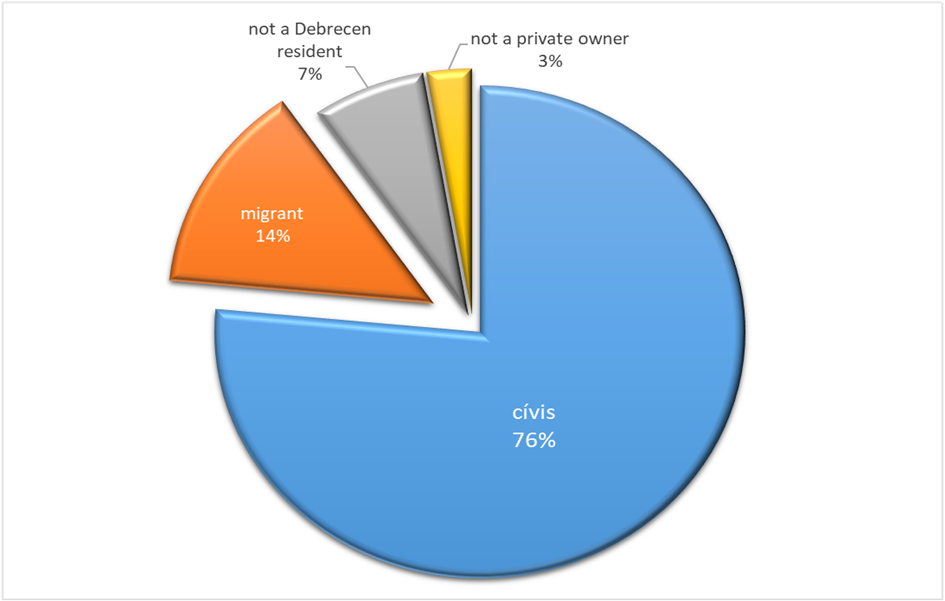

Owners of units of residential property, 1870

By the time of the population census-taking it can be safely stated about the owners of properties inside the “turnpikes” that more than two-thirds (76 %) of them belonged to civis individuals born in Debrecen, although the proprietors of 227 plots (7 %) were natural persons, who were not living in Debrecen and it is not known whether they had acquired their property formerly as Debrecen citizens at that time. In the owner’s rubric of 41 of them the heirs of former Debrecen citizens are found recorded. These cannot with certainty be listed among the Debrecen-born, even if most of them were likely to have been born in Debrecen. 14 % of the owners of plots had been born outside Debrecen and had purchased property in the civis city over the span of decades – especially in the short period subsequent to the Austro-Hungarian Compromise. On the whole an estimated one-fifth of all residential plots having changed hands may well be regarded as a fairly large number of properly in view of the rather short period of time that had elapsed since 1848 or 1867.

A further 3 % (90 plots) were in the possession of the city, or the state, or the Churches, or in that of business organizations. The greatest of them was the Right Honourable City (Municipality) herself (46) her buildings ranging from City Hall, “Ispotály”, (sick- and alms-house) military hospital, the herdsmen’s hall, the cantor-schoolmaster’s residence, or the well-known Hotel Bika all functionally served the community. Apart from the municipal buildings in the city centre, City hall and the Theatre followed the traditional spatial arrangement: the Hospital was built outside the earlier boundary stockade in the south-western direction presenting an expediently sporadic block-like spatial arrangement.

The other major communal proprietor in the city of Debrecen (27) was the Reformed Calvinist Church and the ecclesiastical and other institutions of hers. Besides the church and school buildings owned by the church it used property items for the purposes of vicarage, hospital or even some for commercial purposes. Reformed Church properties were located around two well-defined centres. The Reformed quarter with the Big Church and the Reformed College and their attendant buildings, the ’’Little Church” and the related real property units in Széchenyi street. Apart from those, dispersedly: school building in Kossuth street, residential building in Szent Anna street and the milling house for the hospital in Veres street were held by the Reformed Church.

The Hungarian Royal Treasury (7) owned the the Revenue Office, Customs, stores, Tobacco Exchange, the excisemen’s hostel or the buildings of the above-mentioned higher school of farming. Besides the Roman Catholic Terezianum orphanage, the school and Church in Szent Anna street were also registered as the property of the Piarist Order.

The number of Real property items not held by natural persons

Of the guilds in the city of Debrecen the pig slaughterhouse, the butcher’s and bootmakers’ guilds owned such property. Besides these organizations, The First Debrecen Savings Bank and the Merchantmen's Society’s „Kóroda” (almshouse) were all to be found and operated in the very centre of the city. This range of property owners was closed by the Szilágyi educational institute. Its property was located opposite City Hall, its premises provided place for a pharmacy and a vinegar factory as well.

The spatial pattern of real property not in the possession of individuals

The analysis of the data shows that a channel of in-migration – though a narrow one – was the acquisition of real property. 15-18 % of the intra- urban residential plots got into the hands of in-migrant settlers born outside Debrecen or others who were not Debrecen residents! This can be regarded as a remarkable departure from prior conditions. It was the rental of real property items that had proved to be the main channel of in-migrant settlement and it had become part of civis mentality to highly appreaciate income generated by letting out property units. On the one hand, because of tying property acquisition to citizen rights, permission to settle in was granted, but without privileges (villeins), many were traditionally eligible to obtain residence – while the civis could take advantage of cheap labour and also income from rentals, on the other hand marketers at the Great Fairs of Debrecen showed, from the last third of the 18th century, increasing interest in some kind of residential convenience in the city and the garden areas. The marketmen and the pedlars concluded contracts with the civis concerning residence for the intervening periods between the Great Fairs in order to store merchandise. To their mutual satisfaction the shaping of interpersonal relations included remarkable learning processes as a result of which civis and the outsiders began to develop mutual acceptance resulting in a special pattern in neighbourhood settlement. The civis citizen owners had their houses built in most cases on the street front-line of their inter-city plots. Villeins were permitted to build residential structures at the back of the civis owners’ plots, acquiring the ownership of the superstructure only! Or sometimes they were able to rent housing units of lower standards right behind the residential unit at the street-front which in many cases required the transformation of a farm utility section. Civis and „lodger” – the hierarchic relationship of the citizen owner and the tenant determined before 1848 and even after relaxing and dismantling the privilege sytem, the neighbourhood conditions of those living together.

RESIDENTIAL SEGREGATION OF CIVIS CITIZENS AND IN-MIGRANTS

Where the in-migrants settlers moved inside the civis city was influenced, besides the characteristic civis ownership conditions, by the fact that no legal regulation or legal condition prohibited or limited them in their choice of place of residence apart from their financial means or other considerations of theirs.

If we look at the plots where one of the housing units or one of the households was occupied by Debrecen-born individuals (as well), only in exceptional cases can we find a place where there were no civis occupants (only 41 plots, in all) not taking into consideration the uninhabited plots not concerned by the results of the survey query.

Plots inhabited by the Debrecen-born within the intra-urban area, 1870

Similarly dispersed though slightly less dense was the spatial pattern of residential plot distribution where in-migrants also resided; with only the Piac street and Hatvan street districts west of the axis of the city showing some increased density of plots inhabited by in-migrants, (too).

Plots inhabited by the non-Debrecen-born within the intra-urban area, 1870

Much to the real surprise of the researcher the results of measuring population density the Debrecen-born yielded unexpected findings for a unit of area (150 metres in diametre) compared with what has so far been assumed: the smaller size of sites allotted to new ranges, (hóstát) residential plots, resulted in a more crowded pattern of residence. The fact, however, that the assumed higher density meant mainly indigenous population living in these quarters has not so far been assumable.

The residential density of the Debrecen-born population in the inner city of Debrecen, 1870

The other less expected finding was produced by the inquiry into the density of the in-migrant residents:

Residential density of the in-migrant settlers in the inner-city of Debrecen, 1870

The two-prong approach to measuring density shows that a part of the indigeneous population were gradually squeezed out of the centre of town to the fringes, while the new in-migrants endeavoured to get to the centre just in the process of transition into a bigger city assuming large city downtown functions of a larger centre. This strong concentration of non-indigenous population in the area behind the Big Church is explained by the large number of students admitted to the Reformed College, while the prisoners in the City Hall jail also added to density in the very centre. The residential segregation pattern of the indigenous and the in-migrant settler populations clearly directs attention to the fact that further inquiries are likely to establish that the process of industrialization went hand-in-hand with the marginalization of a considerable part of Debrecen citizenry, while the opportunities offered by market conditions could be exploited by a well-to-do segment of in-migrants joining the narrower civis elite. An unequivoval reading of the geographical pattern is that the dividing lines of former social structures of privileged Debrecen citizens – villeins, outside residents shifted to the structural division of civis elite capable of adjusting to market conditions and getting increasingly wealthy and holding municipal positions and the new business elite of in-migrants as against the massively marginalized indigeneous majority and the in-migrant families in a similar social position.

The recipient and in-migrant societies did not stand juxtaposed like two monolithic blocks. Meanwhile the contemporary social transition caused differentiation which, in turn, polarized traditional Debrecen society; similarly segmented social block-formations can be observed among the in-migrants. The wealthy elites purchased real estate property in the inner city and by establishing their own business enterprises were able to fit into the social structure of Debrecen just gaining strength as a hub of the regional market while a majority of them found a living residing “in the backyard” of plots as rentees in the residential areas of Debrecen joining in the social strata below the elite.